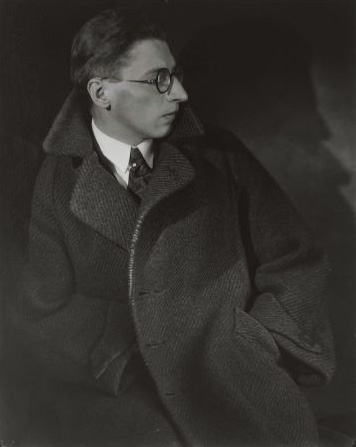

A Visual Analysis of Joseph Sudeks work 'Portrait of my Friend Funke'

Joseph Sudek was born in 1896 in Kolin, about twenty miles from Prague. He became known as the “Poet of Prague”. Sudek was best known for his landscape, still-life and architectural photographs, but also dabbled in portrait taking. In 1924, he took a photograph titled Portrait of my Friend Funke. The photograph itself is a gelatin silver print that is 30.2 by 24.1 centimeters in size. It belongs to the Sonja Bullaty and Angelo Lomano Collection.

Gelatin silver prints were developed in the 1870’s. By 1895 they had mostly replaced albumen prints because they did not turn yellow and were easier to use. Gelatin silver prints are commonly used to make black and white photographs from negatives. They are made by coating paper with a thin layer of gelatin that contains light-sensitive silver salts. After the photograph is exposed to light and processed in chemicals, the photosensitive particles react and change depending on the amount of light that is reaching them through the negative. This will then create a range of blacks and whites in the photograph. Because of their stability and ingenuity, gelatin silver prints are the standard type used for black and white photographs today.

Joseph Sudek’s life surely impacted his interest in photography. After being drafted in the army in 1914, Sudek served in the war until he was wounded in his arm. After his arm became infected, it was amputated at the shoulder. It was after his discharge from the hospital that Sudek began to study photography because he could no longer work at his previous job of bookbinding. He soon joined an amateur photography club; it was in the amateur photography club that Sudek met Jaromir Funke. After both being expelled from the photography club, the two men formed the Czech Photographic Society in 1924. Sudek admired Funke’s intellect, marveling at all that Funke had accomplished even though they were the same age, and that could be clearly seen in the portrait that he took of his dear friend.

In Sudek’s portrait of his friend, Funke is wearing a thick wool overcoat with a dress shirt and tie that is peaking out from beneath it. Interestingly, his coat is unbuttoned, but he is still wearing it for the portrait. His hands are tucked away so that they are not visible and his head is turned to the side. Funke’s facial expression is quite serious and his spectacles are large and circular in shape. His facial features are clearly defined and his hair is neatly brushed back. Funke takes up the majority of the portrait, although there is an interesting background. It appears as though there is a shadow of his profile behind him. Funke is not perfectly centered in the photograph, but he is clearly the main focus. The portrait is very realistic and probably very descriptive of the way Sudek saw Funke. The combination of the glasses, the dress shirt and tie, and the overcoat make Funke appear very serious, sophisticated and intelligent, which was probably Sudek’s goal. He appears to have had a lot of admiration for his friend.

Funke is leaning in one direction and so there is adequate room for his shadowed profile in the background. He appears to be leaning away from the direction in which he is looking and he does not seem completely comfortable in the position that he is in. Still, the portrait does display a sense of order even though he is not directly centered. The white of his dress shirt beautifully contrasts to the grays of his wool coat and the dark behind him. His face is soft and light, but even it appears to be toned with dark and light grays. The cheeks are darker than the rest of his face, perhaps showing that he was blushing when the photograph was taken. Or, perhaps he had just entered from the cold outdoors and Sudek immediately asked him to sit for a portrait before he had a chance to remove his overcoat. This would explain why it is unbuttoned but still on him and why his cheeks are more distinctly toned. Sudek uses light in a fascinating way in the portrait. Funke’s face is strongly lit as opposed to the background, emphasizing his features. The stark white of his dress-shirt opposes the dark behind him and his face is toned in grays in the middle. Even though the portrait is black and white, one can almost see the colors because it is such an intense depiction, with such a great variety of tones and details. Furthermore, it is possible to gain a sense of just how Funke’s wool overcoat felt to the touch because the texture is clear. Similarly, the smoothness of Funke’s face can also be imagined.

Something that is immediately noticeable in the portrait is the way that Funke’s hands are hidden. As it turns out, Sudek had previously lost his right arm and had it amputated at the shoulder. Perhaps he asked Funke to hide his hands in his overcoat, or maybe Funke did so on his own. If Sudek posed Funke in this manner, one has to wonder as to why that would be; even it was subconscious on his part. Still, the way that Funke is seated gives him an aura of originality. It is not like every other forward-facing portrait. Instead, it has more feeling to it than a normal portrait would evoke. By looking at the portrait, one could guess that Funke was a friend of Sudek’s because of the casual way in which he is seated and posed. Sudek captured this moment beautifully and allowed the viewer to picture Funke seated in front of him or her. In creating a casual portrait such as this, the viewer is able to connect with Funke. Clearly, Sudek saw something in his friend that he wanted to capture, and he attempted to show that to the rest of the audience that would be viewing the photograph

Sawyer, Charles. “Joseph Sudek”. Creative Camera: Number 190. April, 1980.

Comments